Be a Hero

“Be the change you want to see in the world” is a tall fucking order.

“Be the change you want to see in the world” is a tall fucking order.

Gandhi never said that, FYI.

I want world governments to take serious action on anthropogenic climate change. I want an end to war. I want millions to not die of starvation every year. I want a fairer distribution of wealth. I am uncertain how to be all those changes in a manner that can have even a modicum of impact. If I dwell on it, the sense of hopelessness, of feeling powerless, is paralyzing.

The song “Powerless” by Grammy-winner Nelly Furtado has the line “This life is too short to live it just for you.” It’s on my running playlist, and for the longest time I misinterpreted it as a breakup song. I figured she was dumping some guy because he’s too needy and life’s too short for that.

That’s not what the song is about.

Furtado sings of releasing yourself from limitations, drawing strength from what is important to you, living a meaningful life. But that “meaningful life” stuff is something humans have struggled with for millennia—it’s kept philosophers in business since Ancient times—and this sense of struggle might be why the next line in the song is: “But when you feel so powerless what are you gonna do?”

What are you gonna do? A lot of people choose to not give a fuck. Not giving a fuck is popular. It’s a problem that arises when you see compassion and love as limited resources. What many don’t realize is that fucks procreate.

I’m not talking about literal fucking to literally procreate, but rather specific adaptation to imposed demands (SAID).

That’s a fitness thing. The SAID principal is that we adapt to the demands we place upon ourselves. When you work at giving more of a fuck, you get better at it, are strengthened by it, rewarded for it, and you develop enhanced performance to give more fucks.

The World Loves a Hero

There is a template for mythological heroism called “The Hero’s Journey.” It was popularized by Professor Joseph Campbell in the mid 20th century via his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. What’s fascinating about Campbell’s work is his revealing of a narrative pattern of the hero’s journey across mythology. Spanning continents and millennia, various peoples of the world who had no contact with one another were telling the same type of story about their mythological heroes again and again.

Campbell called this phenomenon “monomyth.”

You’ll see it in a lot of modern stories as well; George Lucas was heavily influenced by Campbell’s work. My favorite fantasy novels are about a boy whose parents were murdered when he was a baby, and he was raised in secret by his aunt’s family. They hid the knowledge that he was actually a powerful wizard destined to slay the dark lord.

Depending on your age, you may be thinking Harry Potter, but I’m referring to a series from the early 80s called The Belgariad. Much of that premise applies to Luke Skywalker as well.

Campbell outlined 17 stages to the journey, and I’m going to focus on, well, none of them. But Campbell also had excellent insights for heroism in the modern age.

Before addressing the “how” of being a hero, you’ll want to know more about why.

The Logic of Karma

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces Campbell writes that people are overly “self-protective” and we “whitewash, and reinterpret” our bad acts as “the faults of some unpleasant someone else.”

The Nazis thought they were the good guys.

Campbell then explains that such a realization—that maybe we’re not so good—can lead to a moment of revulsion for behaving so basely; it becomes intolerable to the soul.

Regardless of whether souls exist or not, I’m not one to believe that the universe keeps some balance sheet of your virtuous acts and misdeeds then treats you accordingly. Rather, it seems logical to assert that if you cast a net of negativity out into the world, you will catch people in it, and that negativity will be reflected back upon you. In other words, treat people like shit, and they’ll likely treat you the same.

Beyond that, if you do something bad and get away with it, it is reinforcing and can lead to additional bad acts that perhaps become ever more egregious. Such behavior usually catches up to people, in one form or another. Yes, there are examples of the ruthless ruling and never getting comeuppance, but focusing on those is called “survivorship bias;” we see people attain high station via cruelty (often coupled with privilege) and fail to notice the far more numerous invisible ones who were punished for it.

Conversely, cast a net of positivity, and you’ll catch people in that too.

Transmutation of the Social Order

“The modern hero,” Campbell wrote, “cannot, indeed must not, wait for his community to cast off its slough of pride, fear, rationalized avarice, and sanctified misunderstanding. ‘Live,’ Nietzsche says, ‘as though the day were here.’ It is not society that is to guide and save the creative hero, but precisely the reverse.”

Live as though the day were here. Here to do what?

Campbell writes of the world requiring “a transmutation of the whole social order,” which sounds like we’re getting back to one of those “tall fucking order” things again.

But consider chaos theory.

A branch of mathematics examining complex systems sensitive to small changes in initial conditions, chaos theory has been referred to as the “butterfly effect,” a metaphor that lets us imagine the minor air disruption of a butterfly’s wings culminating in tornado formation weeks later. Slight alterations at an earlier juncture can end up yielding widely different results farther down the line.

It’s why we imagine time travel as being so dangerous. Many a science fiction movie—and The Simpsons Halloween special—has examined how traveling back in time and making the smallest change ripples across the continuum, creating massive altering of the present.

And yet, we struggle to believe that a small thing we do in the present will affect the future.

Echoing in Eternity

“What we do in life, echoes in eternity.”

This “famous quote” was said by an actor with an Australian accent pretending to be a Spaniard in ancient Rome. It’s Russell Crowe in Gladiator. He says it to encourage his men to ride into battle and slay the enemy so they can steal their land and enslave their people.

So, perhaps not the most positive of ways to write history.

But the idea of having something we do have a lasting and positive effect is powerful. Living should be more than just existence, more than just taking up space, using up resources, going to work and paying bills and bingeing Netflix. Unless that makes you happy. I’m not the boss of you.

Many wish to feel like they’ve done something important, made a difference. Yet others ask, “What’s in it for me?”

Eternal Rewards?

What happens when you die? Maybe nothing. Maybe something. But one not need be questing for some ethereal reward in the afterlife to justify doing something good today.

Again: what’s in it for me?

In the mid 19th century philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer wrote that morality is based on “the everyday phenomenon of compassion.” He asserts there should be no ulterior motivations. Yeah, that’s a nice idea, but I need to get paid. I’m not saying there aren’t pure acts based on compassion alone, I’m just trying to be realistic and appeal to self-interest as well.

My friend Tim Sanders knows all about how compassion reaps financial dividends. He was a top executive at Yahoo! and wrote the New York Times bestseller Love is the Killer App (in 2002, when people still said “killer app”). The book reveals Tim’s wisdom of how compassionate leadership, building a respectful workplace, and being giving of one’s self is key to winning business and advancing your career.

Self-interest can take myriad form. William James, acknowledged as the Father of American Psychology, recognized the psychological need many have to hold certain beliefs, including the religious. If you behave in a certain way because you think God wants you to, you benefit. Alternatively, if you believe in doing something because it’s right, and it makes you get those warm fuzzies from being good for goodness’s sake, it’s another form of payment.

You can be driven by faith, seeing humans as an essence created by God, or as philosopher and psychologist John Dewey explained in the early 20th century, you can take the view that we are natural beings, evolved organisms inextricably tied to a fundamentally unstable environment that we must struggle to survive and thrive in.

Earlier I was down on the concept of “not giving a fuck,” but forgive me this brief hypocrisy when I attest that I do not give a single fuck which path motivates you, religious or secular, so long as you can do something that makes this world a better place.

A Hero for Today

There is no 17-Stage Hero’s Journey here. Rather, it’s three steps. This is the new hero’s journey for the 21st century, because we’re living as though the day were here, right?

Humans are more likely to be passionately drawn toward something than to flee. I want you to give more fucks, and thereby strengthen your fuck-giving ability, to give even more fucks, because you’re moving toward something good.

Giving fucks. The operative word there, as much as I love it, is not “fuck.” It’s “giving.”

I saw The Who in 2015 for their 50th anniversary tour and wasn’t expecting much. I mean, Roger and Pete are in their 70s. But they gave it their all their fucks, and what a show.

I doubt they needed money. They were paid more by the joy of bringing their art to the world for another tour. For many in the packed arena, me included, it was the first and only time we would see them. They played for us like they knew that.

Bringing others joy through sharing your art is a way of being a hero, FYI.

Let’s segue to my 3-Step Plan to help you Be a Hero.

STEP 1: WHO THE FUCK ARE YOU?

See what I did there?

This step is based on the first part of expectancy-value theory, a model of behavior change developed in the 1960s by psychologist John Atkinson. Simply put, you’re more likely to engage in behaviors you expect to be successful at.

What have you got in you? What can you give?

Where there’s a way or path, it is someone else’s path;

each human being is a unique phenomenon.

—Joseph Campbell, Goddesses

The 20th century philosopher José Ortega y Gasset wrote “The will to be oneself is heroism.”

Phil Cousineau, an author, filmmaker, and expert on the hero’s journey, agrees. He wrote the Introduction to a book on the life and work of Joseph Campbell, and gives this anecdote:

I discovered an uncanny scene that struck me as being at the heart of the hero’s journey. It was that of a crumbling tombstone in Boothill Cemetery in Tombstone, Arizona, the grave marker of an old gunslinger. The epitaph read: “Be what you is, cuz if you be what you ain’t, then you ain’t what you is.”

The 19th century philosopher Søren Kierkegaard explained that to escape despair you must accept your true self. In the 20th century this was expanded upon by psychologist Erich Fromm, who said we must discover our own ideas and abilities, embrace our personal uniqueness, and, most important, develop our capacity to love, which he saw not as an emotion but an interpersonal creative capacity you must actively develop as part of your personality.

“’Know thyself,’” Fromm explained, “is one of the fundamental commands that aims at human strength and happiness.”

I was bullied as a young teen. I’d been a gentle child, and junior high beat that out of me. I created a false exterior of toughness to cope, to fit in. But it wasn’t who I really was, it wasn’t my true strength, and I was not happy. It’s taken decades to deprogram myself from that, to get back to my true self. It’s an ongoing process. Like Fromm said, it’s something one must work at.

Heroic deeds require strength and must be drawn from who you are. But there is more to the equation. Back to Ortega y Gasset, who proclaimed, “I am myself and my circumstances.” These circumstances can be oppressive and limiting.

Oppressive circumstances can be so overwhelming you can barely make it through the day. Sometimes, the heroic deed is putting your own oxygen mask on first, engaging in self-care, so that one day, you may have the ability to help someone else. Sometimes, the person you need to save is yourself, so please take good care.

Engage in self-reflection, and yourself the question: What kind of a heroic deed could I accomplish, considering who I am, and what my circumstances are?

Then take the next step.

STEP 2: EXAMINE YOUR VALUES

This is the second part of expectancy-value theory. It’s not just about what you can do, but what do you want to do? What type of heroic acts can you undertake that hold high enough value for you that you would be motivated to work toward it?

Joseph Campbell wrote in Pathway to Bliss that fulfilling your potential “is not an ego trip; it is an adventure to bring into fulfillment your gift to the world, which is yourself.”

What kind of gift would your true self give?

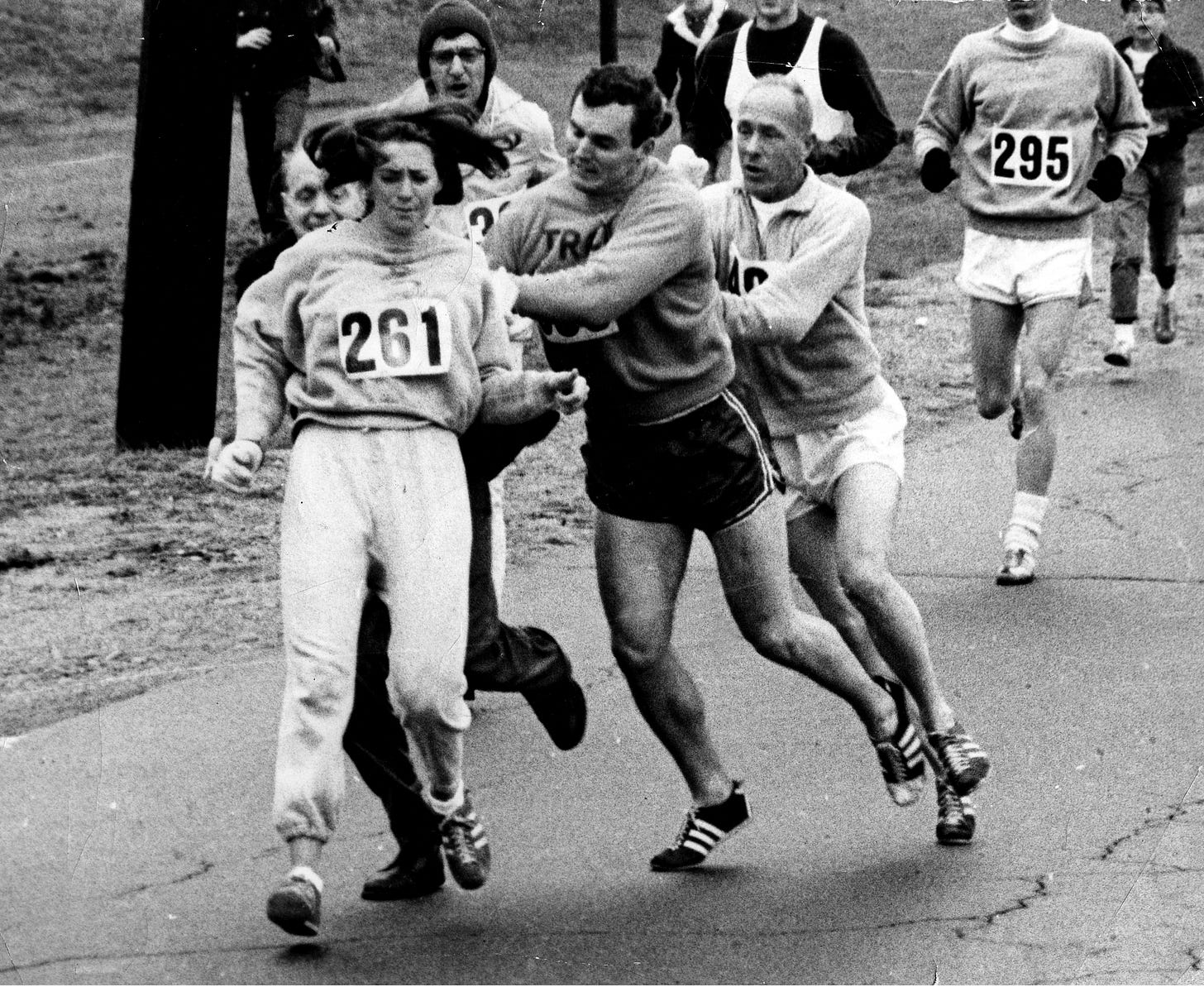

Kathrine Switzer is one of my favorite heroes.

The feature photo for this piece is from the 1967 Boston Marathon, where race official Jock Semple tried to tackle Kathrine because a woman was daring to run a man’s only race. That moment gave Switzer the opportunity to change the world.

Kathrine loves to run; it’s part of who she is. Her circumstances were such that she had been encouraged to run, which was rare for women in the 1960s, and she also had access to a good coach. Another circumstance was those photos being published, making her famous around the world.

And what she valued was the idea of getting more women into running, so she coupled this with her identity and circumstances to make it happen. Five years later, in large part to her efforts, the Boston Marathon was opened to women for the first time. She also played a leading role in finally getting the women’s marathon into the Olympic Games in 1984.

Presently, almost 60% of footrace finishers in North America are women, due in significant part to Kathrine’s efforts. Her heroic mission was born that April day in 1967, and it continues to drive her more than half a century later.

Feel it Still

With all this talk of giving, it’s important to caution about “pathological altruism.” It’s when you put the needs of others so much in front of yourself that you cause self-harm.

Obiwan Kenobi said to young Luke, “You must do what you feel is right.” Twentieth century philosopher Theodor Adorno would add that it’s not just what you feel, but what you think. He extolled that both emotion and intelligence are required for making wise judgements about future actions.

Think on what it is you would value, but don’t forget to examine your feelings about it too. Give to be fulfilled, not drained.

STEP 3: IMAGINE THE ECHO

You are a time traveler, moving forward at a rate of one second per second. What you do today can echo in eternity, making the world better for the people in it.

William James said to “Act as if what you do makes a difference. It does.” But will the actions you take be the “right” ones? Philosopher Richard Rorty wrote in the latter half of the 20th century that there is an absence of absolute moral laws, so instead about worrying over rightness, “what matters is our loyalty to other human beings clinging together against the dark.”

Society can be changed by example. In the fifth century BCE, Confucius wrote, “Sincerity becomes apparent. From being apparent, it becomes manifest. From being manifest, it becomes brilliant.” The famed creator of self-efficacy theory (1977) Albert Bandura would agree. He asserted, “Most human behavior is learned through modeling.”

What we do, what we model, has the power to lead others toward their own heroic journeys.

Beth had a brain tumor, and she died in 1979 at the age of 32. She left behind a husband and two young children. One of those children was an eight-year-old girl.

For a child, losing their mother is one of the most horrible things that can happen. It sets an ache deep into one’s heart that never completely fades. It can have devastating long-term consequences for that person’s mental and physical wellbeing.

But in this case, there were some heroes who made a difference.

During the two years of her mother’s illness, her daughter spent a lot of time in hospitals, and got to know many of the doctors and nurses. She saw how much these people cared, not just for her mother, but for her. They offered her nothing but kindness and compassion, because they wanted to show her that just because this awful thing was happening, it didn’t mean the entire world was horrible.

Because of that experience, the girl came to see that those who cared for the sick were the best of people, the greatest of heroes.

And so, at the age of eight, she was resolved. She would become a doctor. She would heal the sick and do it with compassion and understanding. She would be a hero to those who need it most.

She’s been practicing medicine for over 26 years. She has made many lives better. She has saved lives. To many people, me included, she is a hero. I mean, it takes a lot of courage to be my wife.

Those doctors and nurses will never know the positive effect they had, the chain-reaction they helped initiate, the outcome of their heroic deeds. But what they did, the kindness and compassion they showed, has echoed, and continues to.

Hats, Sandwiches, and Small Acts of Kindness

I have a nice cowboy hat.

I was giving at talk at a Rotary Club during the Calgary Stampede, and excited that for the first time I’d have an excuse to wear my black cowboy hat while giving a presentation. It’s a Calgary thing.

Anyway, I got halfway there and realized I left the damn thing at home.

I lamented this to the club president when I arrived, and without hesitation he removed the cowboy hat from his own head and placed it on mine. He was willing to make the sacrifice of going hatless at a Stampede breakfast, kind of a big deal, for my benefit. It was a small, selfless act that nevertheless moved me. It barely seems to be worth mentioning, and yet, here I am, still pondering how good it made me feel months later.

Recall Bandura: Most human behavior is learned through modeling. Such kindness has ripple effects.

I’ll close with a story about a sandwich.

A few summers ago my son and I went on a road trip to go jump off high cliffs into freezing cold water. On the second day at Sooke River Potholes we were feeling a bit beat up. We had a pool to ourselves, then a young man named Stefan showed up.

His enthusiasm was contagious. My son and I befriended him quickly and we pushed each other to do more and more jumps. It was a great day, made so by Stefan’s friendly demeanor.

Cliff jumping is hungry work.

My son and I have hearty appetites, so I’d made us three sandwiches instead of two. The day before we’d put away three easily. Stefan had not brought a lunch, and without even thinking I offered the third one to him. I mean, he’d made our day by his very presence. How could I not?

It was an insignificant thing, giving a sandwich, but the look he gave me …

There was something in his eyes that revealed such a small act of kindness touched him. I can’t say why, but it was there. For that briefest moment, I was his sandwich-providing hero. I mean, I do make a good sandwich.

Sometimes, that’s all it takes to make a difference to someone, to model good behavior, to change a path in the slightest way, to givesomething of yourself in a way that is valued by others, and by you.

I need a hero. Bonnie Tyler needs a hero. You need a hero. Everyone does. So, go do something heroic, create a bright spot in the world, and those spots will multiply.

No cape required.

Learn about heroes who changed the world for the better in my book On This Day in History Sh!t Went Down.

You can also become a subscriber so you never miss a post like this one:

Thank you so much for this today. You just gave me, a stranger, something I needed without you realizing it. My mother passed away on Monday and quite a lot of what you've shared in this piece resonates. She wasn't a positive person. I try my hardest to be one and this reinforces my resolve to be the positive light that I didn't have. Thank you.

I am a social justice activist. I tend to perceive the world as a whole, and my mind organically wants to focus on "big picture" systemic problems and solutions. My wife is a very practical person, and her mind organically wants to focus on the immediate goings-on around her. She is the most unpretentious person I know. She likes to do things like leave "thank you's" on post-it notes for the janitors at her office, who empty her garbage can every night, but whom she has never met. At holidays, she'll often also leave a foil-wrapped chocolate for them. At one job, the recipient of her notes left a reply. It was a "thank you" and a smiley face, and a heart, scrawled on the bottom of the note she had left. It took me a lot of years of doing the work I do to understand the importance and impact of my wife's "small picture" gestures. It is a basic human need to be seen and valued, yet our culture relegates many to roles where they can be routinely ignored and devalued. The quiet way in which my wife reaches out to people who almost never are thanked -- or acknowledged at all -- for the work the do is a heroic deed. We tend to value big, eventful, news-worthy acts as more worthy than small, day-to-day instances of witnessing and connection, but I have come to believe that both my wife's focus and mine are impactful in different ways, and there is no "heroic" act that is too small to matter. The jury is still out on whether or not I have made the world a better place; there's no doubt that my wife has.